Evidence for the feasibility of machine translation from Tibetan into Chinese

Overview of proposed approach

We have almost no parallel data for Tibetan into Chinese, even including the large web-scraped corpora commonly used for mining machine translation text such as OPUS. Even though Chinese should be close to Tibetan linguistically, and Chinese itself is a high resource language, it is not clear to what extent this can be learned by a transformer in such an extremely low resource setting. Here we aim to provide evidence that this translation problem is, in fact, feasible.

We propose to approach this problem by combining two techniques for training machine translation models: unsupervised machine translation and triangular translation.

Unsupervised translation

Unsupervised machine translation proceeds by first discovering a dictionary between the source and target language. Note that, generally speaking, pre-existing dictionaries intended for human consumption are difficult to use for machine translation. This step may be attempted in a fully unsupervised setting by taking monolingual models for the two languages and trying to align their internal representations of words from monolingual corpora. For previous work on this topic see for example Facebook’s unsupervised MT systems from 2018.

In more detail, all modern NLP models encode text into internal vector space representations that are a kind of universal machine language that represents human text. These internal representations are very high dimensional, typically 768-dimensional or even higher. The monolingual corpora that we already have provide us with a very large set of points in these internal representation spaces simply by using the monolingual models to embed their respective monolingual corpora. We can then try to learn a mapping from the “machine language” space of the Tibetan model to the “machine language” of the Chinese model. This should work as long as these internal representation spaces have similar geometry.

While it is, of course, impossible to visually explore 768-dimensional space, we can nevertheless try to visualize it through dimension reduction techniques. One very recent technique that has become popular and, in our experience, is very effective, is the so-called UMAP1 algorithm. This algorithm is rather complicated and a full description of it is out of the scope of this brief note. Roughly speaking, UMAP attempts to find points in the high dimensional space that “look like” they live on low dimensional (potentially curved) subspaces and project them down to separate 2-dimensional clusters that can then be visually explored.

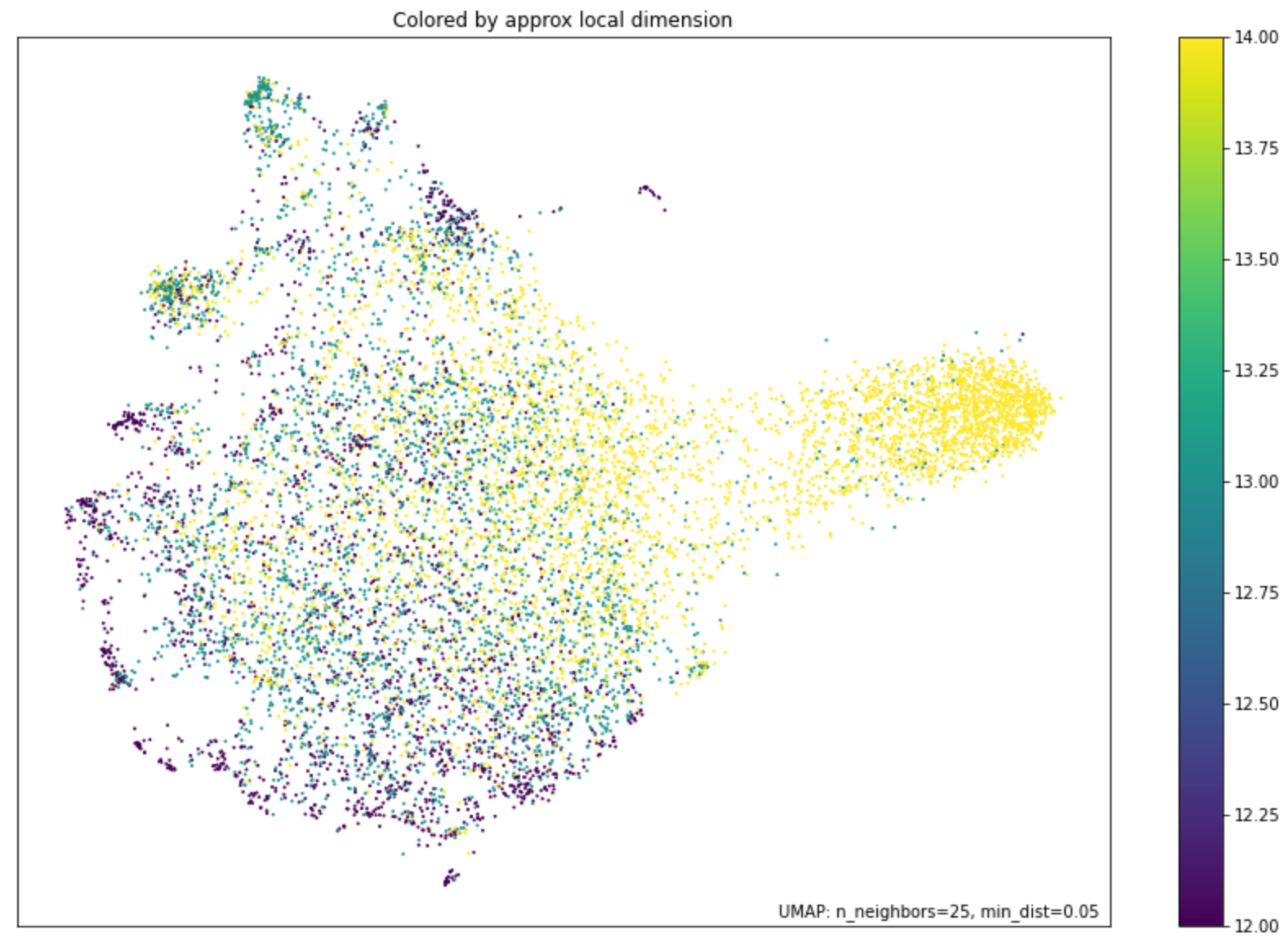

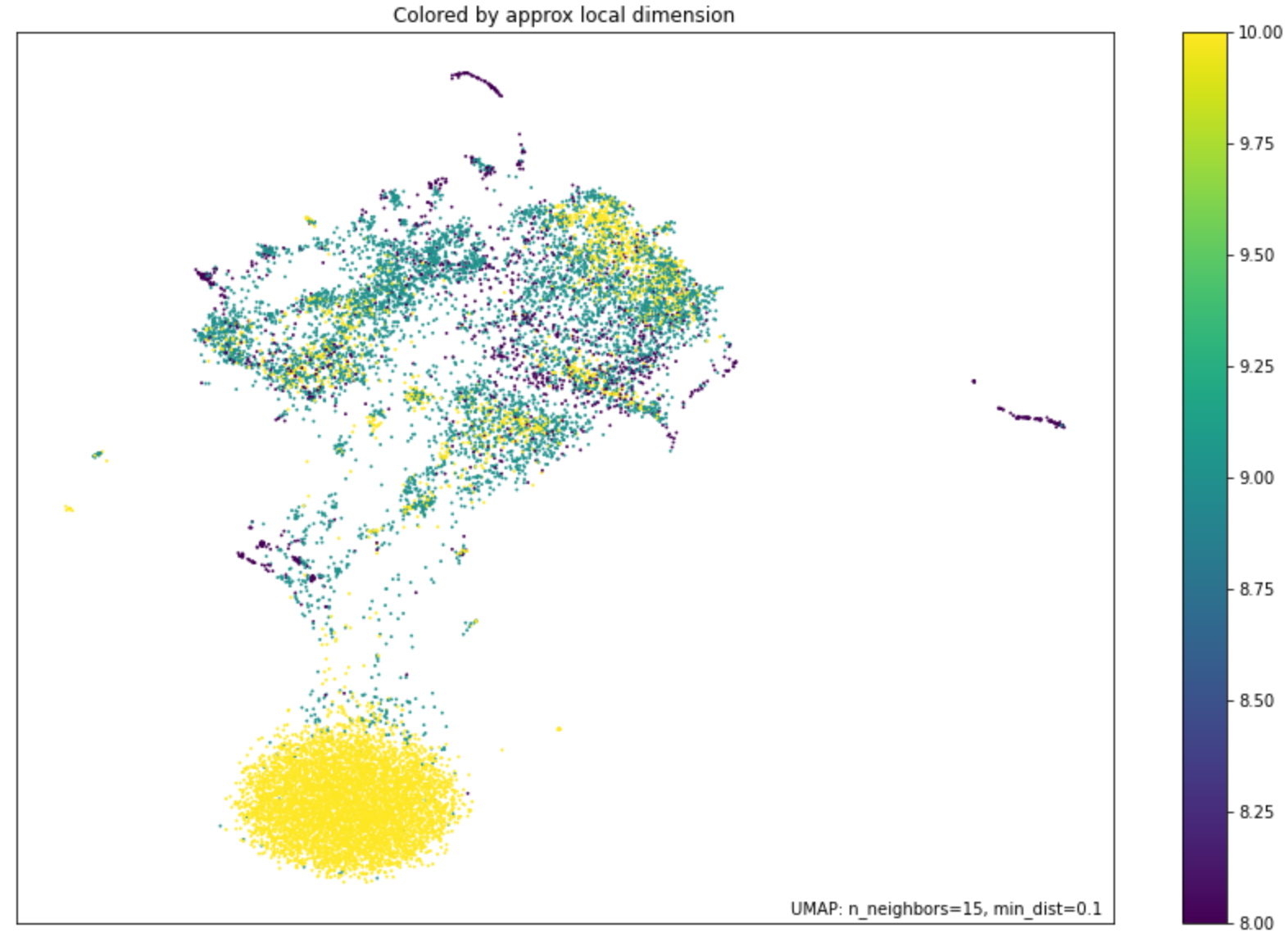

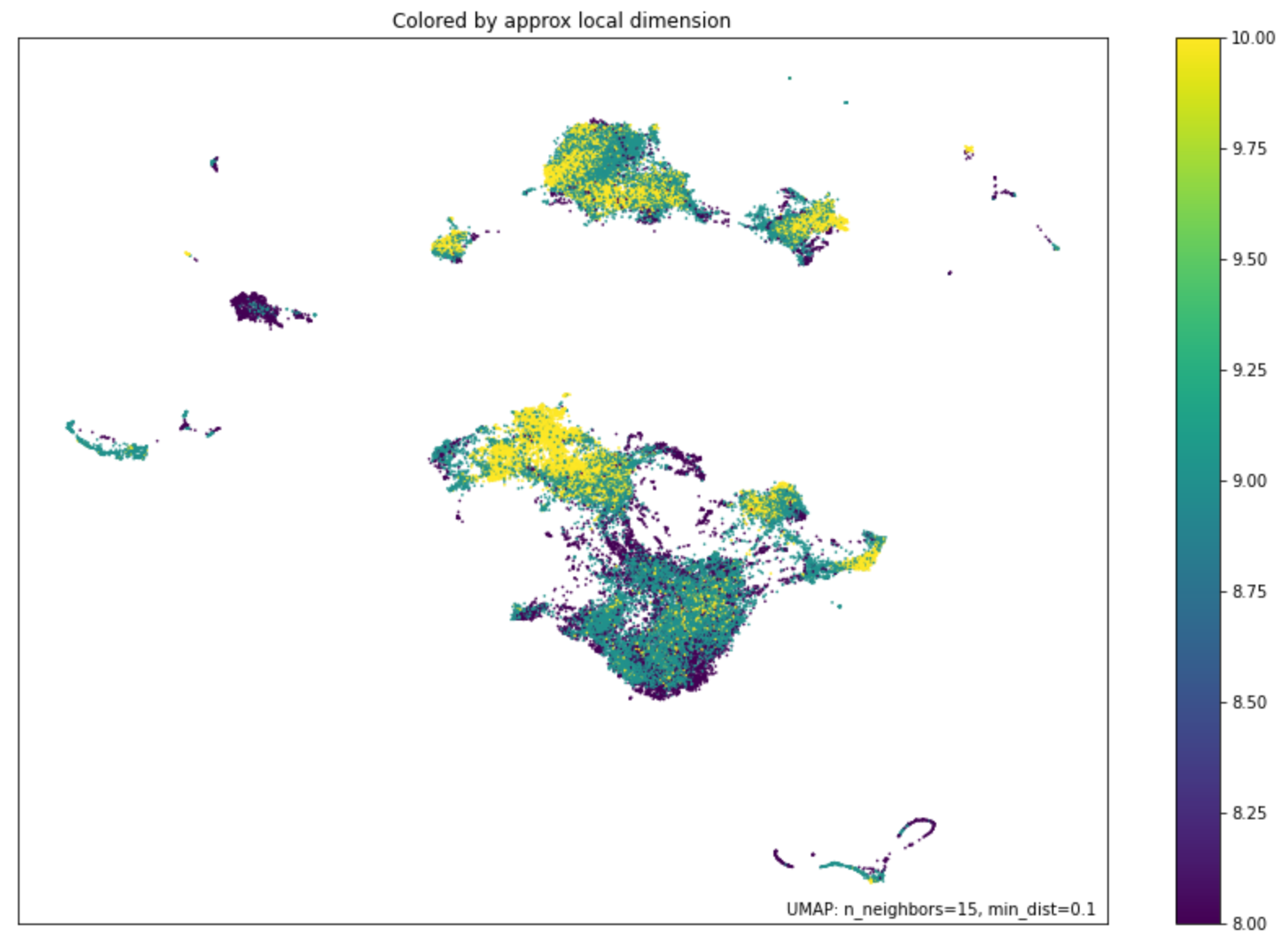

In our experiment, we used UMAP to map out the geometry of token (roughly corresponding to word) embeddings from the trained Chinese and Tibetan models. We used our pre-trained prototype Tibetan transformer, while for Chinese we used the MacBERT model trained by HFL (Joint Laboratory of HIT and iFLYTEK Research) with an extended corpus. We then plotted the UMAP projections, using cosine similarity as the distance metric, of their non-contextual token embeddings for all tokens in their languages. We colorized the UMAP plot by the local dimension of the estimated subspaces, this roughly corresponds to the level of ambiguity of the word/token. For contrast we also include the UMAP results for English. See the results in the three figures below.

Figure: UMAP plot for the non-contextual token embeddings of our pre-trained Tibetan transformer

Figure: UMAP plot for the non-contextual token embeddings of the extended corpus Chinese MacBERT transformer, Hugging Face model name “hfl/chinese-macbert-base”

Figure: UMAP plot for the non-contextual token embeddings of the English RoBERTa transformer, Hugging Face model name “roberta-large”

As we can see, the geometry of the UMAP projections between Tibetan and Chinese looks similar, while English looks much more different. This suggests our linguistic intuition is correct, and also that unsupervised dictionary discovery between Tibetan and Chinese tokens should work well. We may also be able to include an existing human dictionary to improve the results.

Of course, our Tibetan transformer is only a prototype. If we pre-train better Tibetan models that have better tokenization and more faithful token embeddings, we will obtain better token dictionaries.

Once token dictionaries are obtained, they are used to iteratively train translation models on synthetic corpora. These models tend to have a rich vocabulary but sound very “translation-ese”. Fine tuning them on parallel data, such as the 84,000 dataset, should give us a model that incorporates the best of both worlds - the rich dictionary of the unsupervised model and the style of the supervised. Of course, only an actual experiment will decide these hypotheses one way or the other.

Triangular machine translation

While the Tibetan to Chinese direction is extremely sparse, the English to Chinese direction is not. We can exploit any models we have for Tibetan-English and English-Chinese to “complete the triangle” and train a Tibetan-Chinese model.

This is a promising area of current research. There have been some recent papers on triangular translation, for example https://arxiv.org/abs/2203.09027. The competition of the Conference on Machine Translation included a triangular MT category in 2021. Unfortunately, not many teams submitted results. This reflects a natural current preference by the leading labs to focus on co-training and translation of news. The conference continues their push away from news by changing the task.

For triangular Tibetan-Chinese translation there is not much to say other than that we should try various ways to form triangular datasets. Especially important will be to co-train a model for the three languages: Tibetan, Chinese and English. This is a one-time process but is likely to be somewhat expensive, this is reflected in our budget.

Conclusion

We hope to have convinced you that translation into languages other than English, especially Chinese, should be possible. Other languages to consider include, in alphabetical order: French, German, Hindi, Japanese, Korean, Russian, Spanish. Any target language that has a high resource dataset from English can be a candidate.

-

McInnes, L, Healy, J, UMAP: Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection for Dimension Reduction, ArXiv e-prints 1802.03426, 2018, documentation and source code available at https://umap-learn.readthedocs.io/en/latest/ ↩︎